Distributed data modeling refers to choosing how to distribute information across nodes in a multi-machine database cluster and query it efficiently. There are common use cases for a distributed database with well understood design tradeoffs. It will be helpful for you to identify whether your application falls into one of these categories in order to know what features and performance to expect.

Citus uses a column in each table to determine how to allocate its rows among the available shards. In particular, as data is loaded into the table, Citus uses the distribution column as a hash key to allocate each row to a shard.

The database administrator picks the distribution column of each table. Thus the main task in distributed data modeling is choosing the best division of tables and their distribution columns to fit the queries required by an application.

Determining the Data Model¶

As explained in When to Use Citus, there are two common use cases for Citus. The first is building a multi-tenant application. This use case works best for B2B applications that serve other companies, accounts, or organizations. For example, this application could be a website which hosts store-fronts for other businesses, a digital marketing solution, or a sales automation tool. Applications like these want to continue scaling whether they have hundreds or thousands of tenants. (Horizontal scaling with the multi-tenant architecture imposes no hard tenant limit.) Additionally, Citus’ sharding allows individual nodes to house more than one tenant which improves hardware utilization.

The multi-tenant model as implemented in Citus allows applications to scale with minimal changes. This data model provides the performance characteristics of relational databases at scale. It also provides familiar benefits that come with relational databases, such as transactions, constraints, and joins. Once you follow the multi-tenant data model, it is easy to adjust a changing application while staying performant. Citus stores your data within the same relational database, so you can easily change your table schema by creating indices or adding new columns.

There are characteristics to look for in queries and schemas to determine whether the multi-tenant data model is appropriate. Typical queries in this model relate to a single tenant rather than joining information across tenants. This includes OLTP workloads for serving web clients, and OLAP workloads that serve per-tenant analytical queries. Having dozens or hundreds of tables in your database schema is also an indicator for the multi-tenant data model.

The second common Citus use case is real-time analytics. The choice between the real-time and multi-tenant models depends on the needs of the application. The real-time model allows the database to ingest a large amount of incoming data and summarize it in “human real-time,” which means in less than a second. Examples include making dashboards for data from the internet of things, or from web traffic. In this use case applications want massive parallelism, coordinating hundreds of cores for fast results to numerical, statistical, or counting queries.

The real-time architecture usually has few tables, often centering around a big table of device-, site- or user-events. It deals with high volume reads and writes, with relatively simple but computationally intensive lookups.

If your situation resembles either of these cases then the next step is to decide how to shard your data in a Citus cluster. As explained in Architecture, Citus assigns table rows to shards according to the hashed value of the table’s distribution column. The database administrator’s choice of distribution columns needs to match the access patterns of typical queries to ensure performance.

Distributing by Tenant ID¶

The multi-tenant architecture uses a form of hierarchical database modeling to distribute queries across nodes in the distributed cluster. The top of the data hierarchy is known as the tenant id, and needs to be stored in a column on each table. Citus inspects queres to see which tenant id they involve and routes the query to a single physical node for processing, specifically the node which holds the data shard associated with the tenant id. Running a query with all relevant data placed on the same node is called co-location.

The first step is identifying what constitutes a tenant in your app. Common instances include company, account, organization, or customer. The column name will be something like company_id or customer_id. Examine each of your queries and ask yourself: would it work if it had additional WHERE clauses to restrict all tables involved to rows with the same tenant id? Queries in the multi-tenant model are usually scoped to a tenant, for instance queries on sales or inventory would be scoped within a certain store.

If you’re migrating an existing database to the Citus multi-tenant architecture then some of your tables may lack a column for the application-specific tenant id. You will need to add one and fill it with the correct values. This will denormalize your tables slightly. For more details and a concrete example of backfilling the tenant id, see our guide to Multi-Tenant Migration.

Distributing by Entity ID¶

While the multi-tenant architecture introduces a hierarchical structure and uses data co-location to parallelize queries between tenants, real-time architectures depend on specific distribution properties of their data to achieve highly parallel processing. We use “entity id” as a term for distribution columns in the real-time model, as opposed to tenant ids in the multi-tenant model. Typical entites are users, hosts, or devices.

Real-time queries typically ask for numeric aggregates grouped by date or category. Citus sends these queries to each shard for partial results and assembles the final answer on the coordinator node. Queries run fastest when as many nodes contribute as possible, and when no individual node bottlenecks.

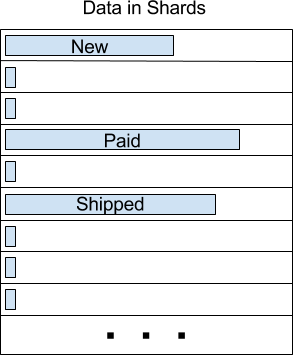

The more evenly a choice of entity id distributes data to shards the better. At the least the column should have a high cardinality. For comparison, a “status” field on an order table is a poor choice of distribution column because it assumes at most a few values. These values will not be able to take advantage of a cluster with many shards. The row placement will skew into a small handful of shards:

Of columns having high cardinality, it is good additionally to choose those that are frequently used in group-by clauses or as join keys. Distributing by join keys co-locates the joined tables and greatly improves join speed. Real-time schemas usually have few tables, and are generally centered around a big table of quantitative events.

Typical Real-Time Schemas¶

Events Table¶

In this scenario we ingest high volume sensor measurement events into a single table and distribute it across Citus by the device_id of the sensor. Every time the sensor makes a measurement we save that as a single event row with measurement details in a jsonb column for flexibility.

CREATE TABLE events (

device_id bigint NOT NULL,

event_id uuid NOT NULL,

event_time timestamptz NOT NULL,

event_type int NOT NULL,

payload jsonb,

PRIMARY KEY (device_id, event_id)

);

CREATE INDEX ON events USING BRIN (event_time);

SELECT create_distributed_table('events', 'device_id');

Any query that restricts to a given device is routed directly to a worker node for processing. We call this a single-shard query. Here is one to get the ten most recent events:

SELECT event_time, payload

FROM events

WHERE device_id = 298

ORDER BY event_time DESC

LIMIT 10;

To take advantage of massive parallelism we can run a cross-shard query. For instance, we can find the min, max, and average temperatures per minute across all sensors in the last ten minutes (assuming the json payload includes a temp value). We can scale this query to any number of devices by adding worker nodes to the Citus cluster.

SELECT minute,

min(temperature)::decimal(10,1) AS min_temperature,

avg(temperature)::decimal(10,1) AS avg_temperature,

max(temperature)::decimal(10,1) AS max_temperature

FROM (

SELECT date_trunc('minute', event_time) AS minute,

(payload->>'temp')::float AS temperature

FROM events

WHERE event_t1me >= now() - interval '10 minutes'

) ev

GROUP BY minute

ORDER BY minute ASC;

Events with Roll-Ups¶

The previous example calculates statistics at runtime, doing possible recalculation between queries. Another approach is precalculating aggregates. This avoids recalculating raw event data and results in even faster queries. For example, a web analytics dashboard might want a count of views per page per day. The raw events data table looks like this:

CREATE TABLE page_views (

page_id int PRIMARY KEY,

host_ip inet,

view_time timestamp default now()

);

CREATE INDEX view_time_idx ON page_views USING BRIN (view_time);

SELECT create_distributed_table('page_views', 'page_id');

We will precompute the daily view count in this summary table:

CREATE TABLE daily_page_views (

day date,

page_id int,

view_count bigint,

PRIMARY KEY (day, page_id)

);

SELECT create_distributed_table('daily_page_views', 'page_id');

Precomputing aggregates is called roll-up. Notice that distributing both tables by page_id co-locates their data per-page. Any aggregate functions grouped per page can run in parallel, and this includes aggregates in roll-ups. We can use PostgreSQL UPSERT to create and update rollups, like this (the SQL below takes a parameter for the lower bound timestamp):

INSERT INTO daily_page_views (day, page_id, view_count)

SELECT view_time::date AS day, page_id, count(*) AS view_count

FROM page_views

WHERE view_time >= $1

GROUP BY view_time::date, page_id

ON CONFLICT (day, page_id) DO UPDATE SET

view_count = daily_page_views.view_count + EXCLUDED.view_count;

Events and Entities¶

Behavioral analytics seeks to understand users, from the website/product features they use to how they progress through funnels, to the effectiveness of marketing campaigns. Doing analysis tends to involve unforeseen factors which are uncovered by iterative experiments. It is hard to know initially what information about user activity will be relevant to future experiments, so analysts generally try to record everything they can. Using a distributed database like Citus allows them to query the accumulated data flexibly and quickly.

Let’s look at a simplified example. Whereas the previous examples dealt with a single events table (possibly augmented with precomputed rollups), this one uses two main tables: users and their events. In particular, Wikipedia editors and their changes:

CREATE TABLE wikipedia_editors (

editor TEXT UNIQUE,

bot BOOLEAN,

edit_count INT,

added_chars INT,

removed_chars INT,

first_seen TIMESTAMPTZ,

last_seen TIMESTAMPTZ

);

CREATE TABLE wikipedia_changes (

editor TEXT,

time TIMESTAMP WITH TIME ZONE,

wiki TEXT,

title TEXT,

comment TEXT,

minor BOOLEAN,

type TEXT,

old_length INT,

new_length INT

);

SELECT create_distributed_table('wikipedia_editors', 'editor');

SELECT create_distributed_table('wikipedia_changes', 'editor');

These tables can be populated by the Wikipedia API, and we can distribute them in Citus by the editor column. Notice that this is a text column. Citus’ hash distribution uses PostgreSQL hashing which supports a number of data types.

A co-located JOIN between editors and changes allows aggregates not only by editor, but by properties of an editor. For instance we can count the difference between the number of newly created pages by bot vs human. The grouping and counting is performed on worker nodes in parallel and the final results are merged on the coordinator node.

SELECT bot, count(*) AS pages_created

FROM wikipedia_changes c,

wikipedia_editors e

WHERE c.editor = e.editor

AND type = 'new'

GROUP BY bot;

Events and Reference Tables¶

We’ve already seen how every row in a distributed table is stored on a shard. However for small tables there is a trick to achieve a kind of universal colocation. We can choose to place all its rows into a single shard but replicate that shard to every worker node. It introduces storage and update costs of course, but this can be more than counterbalanced by the performance gains of read queries.

We call tables replicated to all nodes reference tables. They usually provide metadata about items in a larger table and are reminiscent of what data warehousing calls dimension tables.